In spite of a range of theories and considerable research, scientists so far have not been able to identify a definitive cause for why a person develops Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

However, there are plenty of theories surrounding the potential causes of OCD, involving one of or a combination of either; neurobiological, genetic, learned behaviours, pregnancy, environmental factors or specific events that trigger the disorder in a specific individual at a particular point in time.

We will summarise some of the suggested theories on this page, but before we begin it’s important we make it clear that this is just theory.

There have been many explanations of why people develop OCD. Some have argued that it is inherited, whilst others have said that life events can cause it. Others have suggested that it’s caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain. Different people, different researchers find different explanations more helpful than others. But here’s the point, we simply don’t know!

So let’s summarise some of those explanations.

Biological Factors

Some mental health researchers have encouraged us to think of research on brain scans and similar as indicating that OCD is linked to a genetic or biological cause. This research is often described in terms of chemical imbalances in the brain, faulty brain circuitry or genetic defects.

However, despite the recognition that certain parts of the brain are different in OCD sufferers, when compared with non-sufferers, it is still not known how these differences relate to the precise mechanisms of OCD.

Brain imaging studies have consistently demonstrated differing blood flow patterns among people with OCD compared with controls, and the cortical and basal ganglia regions are most strongly implicated. However, subsequent meta-analysis studies found that differences between people with OCD and healthy controls were found consistently only in the orbital gyrus and the head of the caudate nucleus.

So yes, whilst it’s true to say that sometimes people with OCD are found to have different brain activity, it could be argued this would be expected.

A brain scan is sensitive to different patterns of activity in the brain and can, for example, detect the difference in terms of the way the brain reacts between expert musicians listening to music and people with no special knowledge of music.

These areas of the brain become relevant and ‘switched on’ in particular environments where the person is worrying. It is therefore not surprising that there are brain activation differences between people with OCD and those without; this does not mean that OCD is a biological disease.

PANDAS

A 1998 finding implicated the basal ganglia as a key brain region in OCD with the discovery that in a sub-group of children with OCD the disorder may have been triggered by infections.

Streptococcal infections trigger an immune response, which in some individuals generates antibodies that cross-react with the basal ganglia. The explanation was that some children begin to exhibit OCD symptoms after a severe strep throat infection. It is thought that the body’s natural response to infection, the production of certain antibodies, when directed to parts of the brain might be linked in some way to Paediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders associated with Streptococcal Infection (PANDAS).

This mechanism may explain the subgroup of children in whom OCD develops after a streptococcal infection, and worsens with recurrent infections. However, a later 2004 study found no link between subsequent infections and exacerbation of symptoms.

What we do know is that if OCD results from a strep throat infection the symptoms will start quickly, probably within one or two weeks.

So it could be that PANDAS whilst not a cause for OCD, triggers symptoms in children who are already predisposed to the disorder, perhaps through genetics or other causal explanations.

Genetic Factors

Overall, genetic studies indicate some tendency towards anxiety that runs in families, although this is probably only slight.

Some research points to the likelihood that OCD sufferers will have a family member with OCD or with one of the other disorders in the OCD ‘spectrum’. In 2001, a meta-analytic review reported that a person with OCD is 4 times more likely to have another family member with OCD than a person who does not have the disorder.

This and other studies have raised the possibility of familial prevalence of OCD and led to a search to identify specific genetic factors that may be involved. S However, despite a proliferation of studies, and dozens of potential gene candidates suggested, researchers have so far failed to identify a consistent candidate gene responsible for OCD.

It also needs to be remembered that many sufferers do not identify OCD anywhere else in their family, or even other anxiety problems. This theory could be further questioned based on speaking to identical twins where one will have OCD and the other has no anxiety problem at all.

What this suggests is that genetics may not be the only cause of OCD (if at all), and that family prevalence of OCD could be learned behaviours in some cases. So although we cannot rule genetics out, it’s clear that it’s not the whole story and learned or environment factors may play a more significant part.

In summary, there is no obvious benefit to offering biological explanations for the cause of OCD, especially if such suggestions lead those who suffer to dismiss existing psychological treatment methods.

Chemical Imbalance

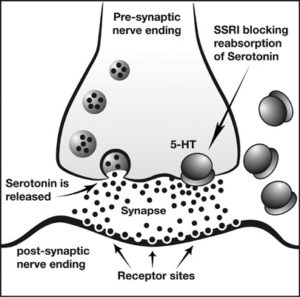

It’s common to see and hear mental health professionals describing the cause of OCD in terms of a ‘biochemical imbalance’. These approaches have focused on one particular neurotransmitter, serotonin.

It’s common to see and hear mental health professionals describing the cause of OCD in terms of a ‘biochemical imbalance’. These approaches have focused on one particular neurotransmitter, serotonin.

Serotonin is the chemical in the brain that sends messages between brain cells and it is thought to be involved in regulating everything from anxiety, to memory, to sleep.

Through the accidental discovery in the late sixties of the effectiveness of the serotonin active tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine, which did not substantially impact on serotonin, led to the serotonin hypothesis.

Initially, it was suggested that there was a gross deficit in serotonin; when this was not actually identified, increasingly subtle abnormalities were suggested, with the evidence overall remaining implausible at best.

In more recent years some researchers have argued that the most robust evidence for the serotonin hypothesis is the specificity of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRI) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medication.

However, given that this effect was the observation that generated the hypothesis, it cannot reasonably be considered as evidence for it.

It’s worth noting that relapse is frequently associated with the withdrawal of SSRI medications in OCD, more so than in other conditions, especially where no behavioural therapy is in place, which is yet to be fully understood. This could mean that serotonin is an important neurotransmitter involved in the maintenance of OCD, if not a specific cause.

Overall, there is a place for SSRIs in the treatment of OCD, especially where co-morbidity is present, provided that medication remains part of informed patient choice, and combined with psychological therapy like CBT.

Psychological Theories

Other research has revealed that there may be a number of other factors that could play a role in the onset of OCD, including behavioural, cognitive, and environmental factors.

For example, according to the Learning Theory, OCD symptoms are a result of a person developing learned negative thoughts and behaviour patterns, towards previously neutral situations which can result from life experiences.

Research has revealed a great deal about the psychological factors that maintain OCD, which in turn has led to effective psychological treatment in the form of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

Behavioural Theory – Learned Theory

During the 50s and 60s researchers reported the successful behaviour treatment of two cases of chronic obsessional neurosis (a forerunner for the Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder name), followed by a series of successful case reports.

This discovery and research heralded the application of psychological models to obsessions and the development of effective behavioural treatments.

This research later proposed that ritualistic behaviours were a form of learned avoidance.

Behaviour therapy for phobias had proved successful in the treatment of phobic avoidance through desensitisation, but attempts to generalise these methods to compulsions had been unsuccessful.

Researchers argued that it was necessary to tackle avoidance behaviours directly by ensuring that compulsions did not take place within or between treatment sessions. This thinking anticipated cognitive approaches in that they emphasised the role of the expectations of harm in obsessions and the importance of invalidating these expectations during treatment, but this was subsequently regarded as peripheral to the major task of preventing compulsions.

Around the same time in the early seventies other researchers developed treatment methods in which exposure to feared situations was the central feature. These differing approaches were subsequently incorporated into a highly effective programme of behavioural treatment incorporating the principles of what we now refer to as exposure and response prevention (ERP).

Support for the use of this method came from a series of experiments in which it was demonstrated that, when a ritual is provoked, discomfort and the urge to ritualise spontaneously subside when no rituals (compulsions) take place.

These researchers elegantly specified the behavioural theory of OCD, that behavioural treatment of OCD is based on the hypothesis that obsessional thoughts have through conditioning, become associated with anxiety that has failed to extinguish.

Sufferers have developed avoidance behaviours (such as obsessional checking and washing), which prevent the extinction of anxiety. This leads directly to the behavioural treatment known as ERP, in which the person is: (a) exposed to stimuli that provoke the obsessional response, and (b) helped to prevent avoidance and escape (compulsive) responses.

An important contribution to the development of ERP was the observation that the occurrence of obsessions leads to an increase in anxiety, and that the compulsions lead to its subsequent attenuation. When the compulsions were delayed or prevented, people with OCD experienced a spontaneous decay in anxiety and the urges to perform compulsions. Continued practice led to the extinction of anxiety. The ‘spontaneous decay experiments’ that demonstrated this were crucial both for therapists and patients to be confident that, if they confronted their fears, anxiety and discomfort would diminish and ultimately disappear.

These early behavioural theories and experiments set the stage for later cognitive-behavioural theory and treatment.

Cognitive theory

Many cognitive theorists believe that individuals with OCD have faulty beliefs, and that it is their misinterpretation of intrusive thoughts that leads to OCD.

According to the cognitive model of OCD, everyone experiences intrusive thoughts from time-to-time. However, people with OCD often have an inflated sense of responsibility and misinterpret these thoughts as being very important and significant which could lead to catastrophic consequences.

The repeated misinterpretation of intrusive thoughts leads to the development of the obsessions and because the thoughts are so distressing, the individual engages in compulsive behaviour to try to resist, block, or neutralise the obsessive thoughts.

The cognitive-behavioural theory developed following a focus on the meaning attributed to internal (or external) events. The cognitive-behavioural theory builds on behavioural theory as it begins with an identical proposition that obsessional thinking has its origins in normal intrusive cognitions. However, in the cognitive theory the difference between normal intrusive cognitions and obsessional intrusive cognitions lies not in the occurrence or even the (un)controllability of the intrusions themselves, but rather in the interpretation made by people with OCD about the occurrence and/or content of the intrusions.

If the appraisal is focused on harm or danger, then the emotional reaction is likely to be anxiety. Such evaluations of intrusive cognitions and consequent mood changes may become part of a mood-appraisal negative spiral but would not be expected to result in compulsive behaviour. Cognitive-behavioural models therefore propose that normal obsessions become problematic when either their occurrence or content are interpreted as being personally meaningful and threatening, and it is this interpretation which mediates the distress caused.

Thus, according to the cognitive hypothesis, researchers have hypothesised that OCD would occur if intrusive cognitions were interpreted as an indication that the person may be, may have been, or may come to be, responsible for harm or its prevention.

Central to how threatening this appraisal is the idea of not only how likely the outcome is, but how ‘awful’ this is to the individual. Furthermore, this is set against the individual’s sense of how they might cope in these circumstances.

According to cognitive models, the interpretation of an intrusive thought results in a number of voluntary and involuntary reactions which each in their turn can have an impact on the strength of belief in the original interpretation. Negative appraisals can therefore act as both causal and maintenance agents in OCD.

Some researchers believe that this theory questions the biological theory because people may be born with a biological predisposition to OCD but never develop the full disorder, while others are born with the same predisposition but, when subject to sufficient learning experiences, develop OCD.

Psychoanalytic Theory

Commonly accepted in the past, but nowadays increasingly disregarded, the psychoanalytic theory suggests that OCD develops because of a person’s fixation arising from unconscious conflicts or discomfort they experienced during infancy or childhood, or the way a person interacted with his or her parents during childhood. This theory is now quite rightly disregarded due to the failure of psychoanalytic therapy to treat OCD.

Stress

Stress and parenting styles are environmental factors that have been blamed for causing OCD, but no evidence is yet to show that. Stress does not actually cause OCD, but major stresses or traumatic life events may precipitate the onset of OCD. However, these are not thought to cause OCD, but rather trigger it in someone already predisposed to the disorder.

If left untreated, everyday anxiety and stress in a person’s life will worsen symptoms in OCD. Problems at school or work, university exam pressures and normal everyday problems that relationships can bring are all contributory factors to increasing the frequency and severity of a person’s OCD.

Depression

Depression is also sometimes thought to cause OCD, although without question depression will make OCD symptoms worse, the majority of experts believe that depression is often a consequence of OCD rather than a cause.

SUMMARY

As you can see there is a range of factors have been identified as contributing to the cause of OCD, and there is still a great deal of theoretical contention surrounding the definitive cause.

However, despite most of the above theories offering compelling and highly informative insights, it’s a possibility that a combination of the theories may eventually be identified as the actual cause of OCD and that it is likely that for any given person a number of factors are involved.

Whilst the cause is currently still being debated, sometimes vigorously by the scientists, what is not in contention is the fact that Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder is indeed a chronic (at times), but equally very treatable medical condition.

It’s also important that we don’t become fixated on what causes our OCD at the expense of fighting and tackling it. Even if we think we have identified a cause, it won’t necessarily help us overcome OCD , so our focus must remain on tackling the problem we have right now, today, in the here and now.

What to read next: