The incidence of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) or Obsessive Compulsive Neurosis as it was once known, is a relatively common disorder and can be traced historically, cross-culturally and across a broad social spectrum and does not appear to restrict itself to any specific group of individuals. On the contrary, evidence shows numerous examples of OCD type symptoms in the lives of figures throughout the ages.

The incidence of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) or Obsessive Compulsive Neurosis as it was once known, is a relatively common disorder and can be traced historically, cross-culturally and across a broad social spectrum and does not appear to restrict itself to any specific group of individuals. On the contrary, evidence shows numerous examples of OCD type symptoms in the lives of figures throughout the ages.

People experiencing problems with obsessions and compulsions (what we now call OCD) will have probably been around since people have been around. Finding early historical descriptions of OCD does exist, with some clear detailed likely cases dating back to the 14th century, some of which we will look at below.

Of course the name OCD did not come into being until the 20th century, but prior to that earlier references to symptoms we would now call Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder were surprisingly called scrupulosity.

Much of the earlier historical record of OCD descriptions are in the religious, rather than the medical literature, and what is clear from the cases we have found, is that from the in the 14th and 18th century, obsessional fears around religion were commonplace. So around this time, a new word for obsessions and compulsions came into usage, scrupulosity. Later in the seventeenth century, obsessions and compulsions were also described as symptoms of melancholy.

Scrupulosity is a modern-day psychological problem that echoes the traditional use of the term ‘scruples’ in a religious context, to mean obsessive concern with one’s own sins and compulsive performance of religious devotion, where in earlier centuries it encompassed all types of obsessions and compulsions. The term is actually derived from the Latin ‘scrupulum’, a sharp stone, implying a stabbing pain on the conscience. The use of the term dates back centuries, with several historical and religious figures suffering from doubts of sin, and expressing their obsessional suffering. Running through some of those historical and religious figures in chronological order.

There is evidence that Jean Charlier de Gerson (1363–1429), the French scholar, educator, reformer, and Chancellor of the University of Paris was concerned with scrupulosity. It’s suggested he warned against the negative effects of too much scrupulosity. The theologian John of Dambach, who influenced Gerson considerably, plainly stated that many high-ranking people had become afraid of making decisions because of excessive scruples.

The German theologian Johannes Nider (1380–1438) wrote what could have been scrupulosity in Consolation of a Timorous Conscience published in 1494 where he presented scrupulosity as a potentially lethal affliction which could generate the life-threatening sin of despair, in which he described a nun from Nuremberg named Kunegond who was in constant fear that her confession was insufficient. This inordinate fear that she had committed a mortal sin, compounded by excessive fasts, not only caused her confessors to be concerned for her sanity but actually delivered her to death’s door.

The Italian Dominican friar and Archbishop of Florence, Antoninus of Florence (1389–1459) described the “scrupulous conscience” as beset by indecision resulting from wild, baseless fears that one has not prayed or otherwise acted according to God’s wishes, which can be caused by either the devil or physical illness. Antoninus’s belief that scrupulosity sometimes had a physical cause, and not necessarily a satanic one, was one of the earliest documented realisations that maladies of thought and behaviour were illnesses necessitating “medicine or other physical remedies” as he put it. He recommended that those trying to escape religious compulsions receive God’s grace, study sacred Scripture, pray constantly, and put up a spirited resistance to the urge to pray or confess excessively. He also, cited approvingly the views of Jean Charlier de Gerson, a fourteenth-century theologian and scholar, that extreme scrupulosity is like a pack of “dogs who bark and snap at passers-by; the best way to deal with them is to ignore them and treat them with contempt”— a fantastic early example and advice for dealing with unwanted obsessions!

Saint Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556) the Spanish Basque priest, theologian and founder of the religious order called the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) wrote “After I have trodden a cross formed by two straws, or after I have thought, said, or done some other thing, there comes to me from ‘without’ a thought that I have sinned, and on the other hand it seems to me that I have not sinned; nevertheless I feel some uneasiness on the subject, inasmuch as I doubt and do not doubt. That is a real scruple and temptation which the enemy sets.”

That description captures the obsessional doubting he may have had. It’s also reported that he later noted “that devout people need to be sure that they have pleased God and that they have not sinned. If unable to convince themselves of this, they may perform acts of penance. If these, too, fail to allay their anxiety, then they will be tormented by doubts and preoccupied by rituals.”

Another to make possible early descriptions of OCD was the Church of England cleric Jeremy Taylor (1613–1667) who in 1660 wrote “of those persons who dare not eat for fear of gluttony; when they are married they are afraid to do their duty, for fear it be secretly an indulgence to the flesh and yet they dare not omit it for fear they should be unjust.” He also referred to obsessional doubting when he wrote of “scruples”, he commented “is trouble where the trouble is over, a doubt when doubts are resolved.”

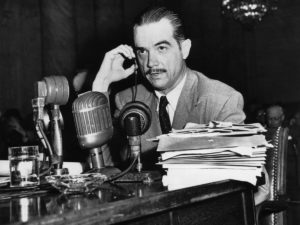

18th-century engraving of Richard Baxter, after a 17th-century portrait by John Riley published in 1763.

Richard Baxter (1615–1691) from Shropshire was a church leader, poet and theologian who wrote at length about melancholy and scrupulosity, “Some melancholy, conscientious persons are still accusing themselves, through mere scrupulosity; questioning almost all they eat, or drink, or wear, or do, whether it be not too much or too pleasing. But it is a cheerful sobriety which God requireth, which neither pampereth the body, nor yet disableth or hindereth it from its duty ; and not an unprofitable, wrangling scrupulosity.” More than just writing about it, Baxter also gave ‘directions’ to those with ‘melancholy’ about their thoughts, and wrote at length about what he identified to be the melancholy and offered directions to help those with melancholy. Arguably one of the first self-help guides for people with OCD? Fascinatingly, his ‘directions’ were for the friends around them, he wrote “When this disease is gone very far. directions to the persons themselves are vain, because they have not reason I and free-will to practise them ; but it is their friends about I them that must have the directions. But because with the most of them, and at first there is some power of reason left, I give directions for the use of such”. We will take a closer look at Richard Baxter’s writings in a separate feature later in the summer.

John Locke (1632–1704) was a philosopher and physician who was widely regarded as one of the most influential of enlightenment thinkers and in 1678 it’s reported that he drafted a letter on the subject of scrupulosity. In one of his letters he wrote, “I cannot imagine that God, who has compassion upon our weakness and knows how we are made, would put poor men, nay, the best of men, those that seek him with sincerity and truth, under almost an absolute necessity of sinning perpetually against him, which will almost inevitably follow if there be no latitude at all allowed as in the occurrences of our lives.”

One of the first known public presentations of what we now call OCD happened in 1691 when John Moore (1646–1714), the bishop of Norwich (later Bishop of Ely) preached before Queen Mary II on “religious melancholy” describing good moral worshippers who are tormented by “naughty and sometimes blasphemous thoughts” despite all their efforts to stifle and suppress them. He describes the scrupulous as having a “fear, that what they do, is so defective and unfit to be presented unto God, that he will not accept it naughty, and sometimes blasphemous thoughts, start in their minds, while they are exercised in the worship of God, despite all their endeavours to stifle and suppress them, the more they struggle with them, the more they increase.” It’s also suggested that Moore had noted of those that were scrupulous were “mostly good people, for bad men rarely know anything of these kind of thoughts”. In addition to such insight about the characters of people affected, from the quote it’s clear that what Moore had succinctly identified that the compulsions people used to stop their blasphemous thoughts were in vain.

As mentioned earlier much of the historical record of OCD descriptions are in the religious, rather than the medical literature. At the time religion was very much a prominent feature of everyday life and with OCD often fixating on things that are important to a person, it’s not surprising that many early accounts are religious based. Historically, it was not unusual for someone with ailments to turn to their local religious figures, who would become very familiar with some health issues, including issues of the mind, like scrupulosity, because of their day-to-day dealings with their parishioners rather than physicians.

Exploring alternative methods to treat OCD is not unique to the present day, in some of the earlier writings there is discussion about how doctors used bloodletting (also called phlebotomy) to treat bad thoughts. This widely used technique of the age involved draining blood from the patient in an effort to adjust the bodily ‘humors’. Ancient origins believed certain human moods, emotions and behaviours were caused by an excess or lack of body fluids (called “humors”): blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm.

As time moved on, physicians of the 1700s and 1800s described more types of behaviours including washing, checking, obsessive fear of syphilis, aggressive and sexual obsessions, but fewer religious obsessions were reported than in earlier centuries.

Modern concepts of OCD began to evolve in the nineteenth century, when theories like faculty psychology, phrenology and mesmerism were popular and when ‘neurosis’ implied a neuropathological condition. Back then when physicians were struggling to understand the mentally ill, they were influenced by intellectual currents coursing through philosophy, physiology and political thought.

Obsessions, in which insight was preserved, were gradually distinguished from delusions, in which it was not. Compulsions were distinguished from impulsions which included various forms of paroxysmal, stereotyped and irresistible behaviour. Influential physicians disagreed about whether the source of OCD lay in disorders of the will, the emotions or the intellect.

In his 1838 psychiatric textbook, the famous French psychiatrist Jean Etienne Dominique Esquirol (1772–1840) described OCD as a form of monomania, or partial insanity. Monomania is a term used to describe psychiatric conditions where the focus of pathology is in one specific area of dysfunction but the rest of the personality and intellect remain intact. Esquirol wrote ‘Monomanic patients presumably can function normally in all other areas except the affected part’. Thus, Esquirol recognised that OCD patients were capable of functioning in many areas of life. Furthermore, he realised that OCD patients continued to have insight, unlike other monomanic conditions such as pure paranoia. Esquirol however could not settle on the issue of whether obsessions were a thinking disorder (disorder of the intellect) or a disorder of the volitional faculty, in other words inability to resist the “the involuntary, irresistible and instinctive activity.” The problem with the concept of volition is that it is not easily measurable; it has philosophical connotations and also can easily be interpreted in a judgmental way.

French psychiatrists abandoned the concept of monomania in the 1850s. They attempted to understand obsessions and compulsions within various broad categories we now identify as conditions such as phobias, panic disorder, agoraphobia, hypochondriasis, manic behaviour and even some forms of epilepsy.

Another French psychiatrist, Henri Dagonet (1823–1902) considered compulsions to be a kind of impulsion and OCD a form of ‘folie impulsive’ (impulsive insanity). In this illness, violent, irresistible impulses overcame the will and manifested in obsessions or compulsions. He described the phenomenon as follows: “the more one tries to discard an idea, the more it becomes imposed upon the mind, the more one tries to get rid of an emotion or tendency, the more energetic it becomes.” Although Dagonet considered OCD as an impulse control disorder, he saw it as a disorder and failure of the will to control these impulses; this concept is different from the irresistible impulses that occur under conditions of organic pathology, such as the epilepsies or damage to the frontal lobes.

Because excessive doubting was a common feature of the condition, and with this inability to tolerate doubt and uncertainty that often drives OCD, it was thought to be unofficially known as the ‘doubting disease’ for many years from a French translation years before, but that English translation may have been slightly confused from the original French meaning. Writing in 1850, the French psychiatrist, Jean-Pierre Falret (1794–1870) used the term folie du doute, which translates to ‘madness of doubt’, and in 1875 another French psychiatrist, Henri Le Grand du Saulle (1830–1886) published a book called La folie du doute avec délire du toucher, which translates to ‘The madness of doubt with delirium (delusions) of touch’. Of course it’s possible the French were calling OCD the doubting disease around that same time, but that’s the closet translation we could find from the period, but we will keep looking.

Just before we move on from Falret, it’s worth mentioning his commitment to drive change for the mentally ill. He was a fierce opponent of psychiatric reductionism which depriving patients with mental health problems of their rights. Falret fought against injustice by proposing a deeply humane approach respecting those with mental health problems. It’s said that in 1835 Falret visited asylums in England and Scotland and actively contributed to the preparation of the lunacy legislation of June 30, 1838 aimed to re-establish the civil rights of the mentally ill.

He was a indeed a true, and perhaps unique, advocate of the time for those with mental health problems and it’s suggested that he said “the mental patients could be cured and that providing them with their place in society and workplace would guarantee their safety”.

But Bénédict Augustin Morel (1809–1873), another French psychiatrist (although born in Vienna) placed OCD within the category, “delire emotif” (diseases of the emotions), which he believed originated from pathology affecting the autonomic nervous system. He felt that attempts to explain obsessions and compulsions as arising from a disorder of intellect did not account for the accompanying anxiety.

By the end of the 19th century and early 20th century, concepts of heredity and degeneration were taking hold in a number of institutions, partly as a result of the discovery of genetic principles by Gregor Mendel. The French psychiatrist Valentin Magnan (1835–1916) considered OCD a “folie des degeneres” (psychosis of degeneration), indicating cerebral pathology due to defective heredity. Since abulia, or the lack of will or initiative, is seen in neurological states (such as strokes), and a disorder or failure of will was seen as part of the obsessive clinical picture, the argument could be made that OCD is a degenerative disorder of the brain and (based on the family studies), of hereditary origin. This concept of neurodegeneration did little to reduce the stigma associated with mental illness in general, but to those already secretive and hypersensitive because of their obsessive and compulsive behaviours, this was an additional reason to hide their disease, and perhaps why into the end of the 20th century OCD was still considered ‘the secret illness’.

While the emotive and volitional views held sway in France, German psychiatry regarded OCD, along with paranoia, as a disorder of intellect (i.e., a disorder of thinking). In 1868, the German neurologist and psychiatrist Wilhelm Griesinger (1817–1868) published three cases of OCD, which he termed “Grubelnsucht,” a ruminatory or questioning illness (from the Old German, Grubelen, racking one’s brains).

In 1877, the German psychiatrist, Karl Friedrich Otto Westphal (1833–1890) ascribed obsessions to disordered intellectual function. His description of a “compelled idea” captures both the cognitive and compulsive aspects of the disorder. Westphal’s use of the term Zwangsvorstellung (compelled presentation or idea) gave rise to our current terminology, since the concept of “presentation” encompassed both mental experiences and actions. In fact, Westphal was the first to describe OCD as it became defined in the classification manuals, including integrity of intelligence, absence of effective causal pathology, inability to suppress the intrusive thoughts, and recognition of the bizarreness of the representations.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the diagnostic category, neurasthenia (a term that was first used at least as early as 1829 to label a mechanical weakness of the nerves), engulfed OCD along with numerous other disorders, but as the twentieth century opened, both Pierre Janet (1859–1947) and Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) isolated OCD from neurasthenia.

In his highly regarded work, Les Obsessions et la Psychasthenie (Obsessions and Psychasthenia), the pioneering French psychologist Janet proposed that obsessions and compulsions arise in the third (deepest) stage of psychasthenic illness. Because the individual lacks sufficient psychological tension (a form of nervous energy) to complete higher level mental activities (those of will and directed attention), nervous energy is diverted into and activates more primitive psychological operations that include obsessions and compulsions.

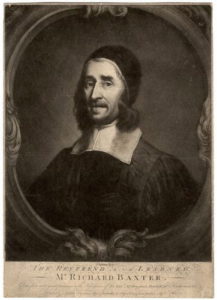

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), the Austrian founder of psychoanalysis, photographic portrait by Max Halberstadt, c. 1921.

Sigmund Freud, the Austrian founder of psychoanalysis, gradually evolved a conceptualisation of OCD that influenced and then drew upon his ideas of mental structure, mental energies, and defence mechanisms. In Freud’s view, the patient’s mind responded maladaptively to conflicts between unacceptable, unconscious sexual or aggressive id impulses and the demands of conscience and reality. He believed obsessive-compulsive behaviour is linked to unconscious conflicts manifested as symptoms of the illness. Conflict develops between the desires and subsequent actions of the conscious and unconscious minds. OCD sufferers, frequently “compelled” to carry out actions giving only temporary relief from anxiety, still “know” it is ridiculous or embarrassing to do so.

In 1895, the term obsessive neurosis “zwangsneurose” was first mentioned in Freud’s paper about “anxiety neurosis”, the term obsessive neurosis was still used by psychiatrists well into the 1990s. But that term zwangsneurose is where the name OCD originated, it was what Freud who called the obsessive and compulsive illness ‘Zwangsneurose’, echoing the coinage of Austro-German psychiatrist Richard Freiherr von Krafft-Ebing, who referred to ’irresistible thoughts’ as ‘Zwangsvorsfellungen’.

In the UK, Zwang, which would be translated usually to ‘forced’ was instead translated as ‘obsession’, but in the United Stated it was translated as ‘compulsion’, so Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder emerged as the eventual compromise at some time in the mid 20th century.

Interestingly, although today health professionals emphasise the dual nature of the illness, obsessive thoughts trigger anxiety, leading to a compulsive action, those earlier health professionals saw it as a single entity.

In his study, Further Remarks on the Neuro-psychoses of Defence Freud proposed a revolutionary theory for the existence of obsessional thinking in which he defined obsessive ideas as “transformed self-reproaches that have re-emerged from repression and that always relate to some sexual act that was performed with pleasure in childhood”. Freud developed a concept of obsessive neurosis that influenced and then drew on his ideas of mental structure, mental energies, and defence mechanisms. This concept included intellectualisation and isolation (warding off the effects) associated with the unacceptable ideas and impulses, undoing carrying out compulsions to neutralise the offending ideas and impulses and reaction formation (adopting character traits exactly opposite of the feared impulses).

A great proportion of Freud’s thinking about obsessive neurosis was formulated in 1909 with his famous description of the case of “The rat man” in which Freud described the psychoanalytical treatment of a 29-year old man who developed certain impulses (Zwangshandlung) against aggressive and sexual obsessions since his early childhood. Later in his life, the patient came across a senior military officer who conveyed a particularly sadistic method of punishment that involved confining rats and placing them in the victim’s anus. At this moment, Freud’s patient reportedly started obsessing that his dead father and a young lady he liked could have suffered this type of torture. Although the patient expressed horror as he mentioned it in his analysis, Freud interpreted it as one of “horror at pleasure of his own desires, of which he himself was unaware.” The precipitating cause of this man’s obsessions was never clearly identified by Freud or by the patient himself, but Freud correlated them to the patient’s ambivalent feelings (hate—love) about his father and his doubts concerning sexual orientation.

Freud’s theories about such matters continued to be fairly well-accepted up to the 1960 and 1970s. In the 1970s behavioural psychology and later cognitive psychology (both discussed more on the cause of OCD page) began to overcome the Freudian theory and other ideas still floating around at that time, to become the main models for understanding OCD that remain so to this day.

We can understand some of this history better by looking at case studies of well-known people that are thought to have been suffering with, what we call today, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Whilst we will never know for sure, there’s enough anecdotal evidence to suggest some or all of these people might have been affected by Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Click each link to read more about the evidence for each individual’s possible diagnosis of OCD.

- Martin Luther (1483–1546)

- John Bunyan (1628–1688)

- Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709–1784)

- Charles Darwin (1809–1882)

- Nikola Tesla (1856–1943)

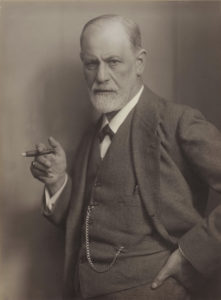

- Howard Hughes (1905–1976)

- Katharine Hepburn (1907–2003) * Insufficient and unproven evidence to suggest had OCD, but listed so we could bust this widely reported myth and link to OCD.

There are of course many well known living celebrities that have in recent years been reported to be suffering from the illness, or taken up the growing trend of claiming to be a ‘bit OCD’. Many of these claims cannot be verified with any degree of accuracy as to a diagnosis of clinical Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, however for interest we have listed some of those well-known, famous people (still living) here.

What to read next: