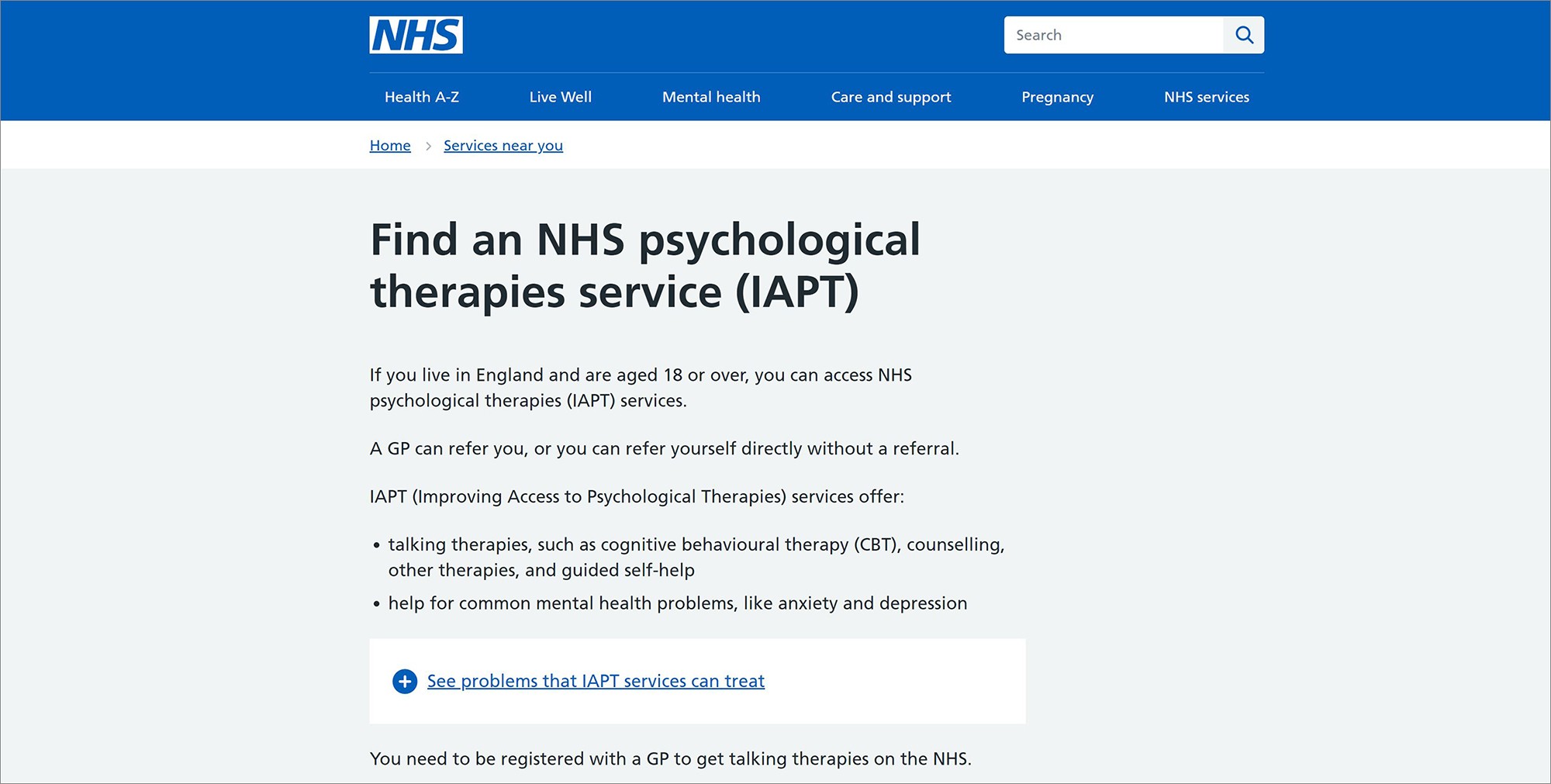

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies or IAPT for short, (pronounced eye-apt), is a programme which began in 2008 with the direct objective to, as the name suggests, improve access for people with anxiety and depression, including OCD, to evidenced based psychological therapies, such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies or IAPT for short, (pronounced eye-apt), is a programme which began in 2008 with the direct objective to, as the name suggests, improve access for people with anxiety and depression, including OCD, to evidenced based psychological therapies, such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

Since then the IAPT programme has transformed treatment of adult anxiety disorders and depression in England, with over 900,000 people accessing IAPT services each year, in the last annual IAPT report (covering the years 2016-2017), 15,048 people entered treatment for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder as their primary problem. IAPT set itself the ambitious target of achieving a minimum of 50% recovery for all individuals completing treatment. In that 2016/2017 report, it’s claimed that 49.7% of those completing a course of treatment had moved to some level of recovery.

It is widely accepted that the IAPT programme is a success based off its original objectives and the NHS has committed to further expanding IAPT services, so 1.5 million people per year will be seen by 2020/21. This represents around a quarter of the community prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders which is indeed ambitious.

So what level of stepped care does IAPT offer?

The initial step will offer help in recognition and diagnosis of a person’s OCD, and provide guided self-help materials. Whilst for most people with OCD, we believe this will not be sufficient, certainly earlier diagnosis and education and knowledge of the illness is beneficial.

IAPT will have two types of psychological therapy practitioners . For steps 1 and 2, these will be low intensity therapy workers trained in cognitive behavioural approaches for people with mild to moderate anxiety and depression. Moving up the stepped approach to level 3, there will be IAPT high intensity therapists trained in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

To try and explain the IAPT stepped care approach to treatment this illustration offers a visual guide.

However, despite the success of IAPT, OCD-UK continue to hear of problems and poor IAPT experiences for many service-users. We want to see these problems addressed and not dismissed, they include:

What are OCD-UK doing to improve problems?

Despite the many problems highlighted above, OCD-UK remain supportive of the overall objectives of the IAPT programme. We’re focused on, where possible, doing all we can to help IAPT succeed so that it can successfully treat and help more people with OCD move to recovery. The fact we spent thousands of pounds on time and resources in 2016 to create the IAPT database shows our commitment to IAPT. In 2018 we have been liaising with senior clinical IAPT staff at NHS England, and will continue to work with them moving forward to help them improve the patient experience.

As part of this programme we’re writing a best practice guide for IAPT services when treating people with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. The purpose of this document will be to help IAPT services understand what is expected by both OCD-UK and the official IAPT manual when treating OCD. This best practice guide will also focus on making recommendations to improve patient experience (not just those with OCD), and is already inviting feedback from users with OCD that have accessed IAPT services in the past.

Once published, our guide will be shared with IAPT services and NHS England and we hope they will take on board and implement any of the key points highlighted. We hope to publish this document later in 2018.

The history of IAPT

The IAPT programme was a direct response by the Department of Health, under the then Labour government, to the arguments put by economist Professor Lord Richard Layard in 2006, in The Depression Report, published by the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics. It followed meetings with clinical psychologist, Professor David Clark, who argued that mental health-related long-term sickness absence cost the national economy far more than a properly funded psychological therapy service that got them back on their feet, earning and paying tax again would.

Following on from Professor Layard’s report, the IAPT programme was established with two demonstration sites in Doncaster and Newham in 2006. On World Mental Health Day in 2007, the then Secretary of State for Health, Alan Johnson, announced substantial new funding of £173 million to fully implement the IAPT programme over the subsequent three years. Subsequently, consecutive governments have supported the IAPT programme with additional funding.

In December 2010, Paul Burstow, the then Minister for Care Services, announced an extension to the IAPT project to include Children and Young Peoples services. The coalition conservative and liberal democrat government pledged £118m annually from 2015 to 2019 to increase access to psychological therapies services to children and young people.

New IAPT Manual

June 2018In June 2018, NHS England launched the IAPT manual, partly intended to address some of the problems we ourselves have listed on this page. The manual was produced to help commissioners, providers and clinicians of services that deliver psychological therapies to improve the delivery of, and access to, evidence-based psychological therapies.

The job of OCD-UK where resources allow and NHS England over the coming months is to encourage CCGs and IAPT providers to adhere to the manuals recommendations and hold those that don’t to account.

Access the ManualBlog – A guide to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies services

June 2018The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) Manual is the definitive source of information on how to set-up and deliver excellent IAPT services, says Professor David M Clark.

Read the blog

What to read next: