Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a serious anxiety-related condition that affects 1.2% of the population, which is around three quarters of a million people here in the UK based on current estimates. Together with their families, who support people with OCD, and are frequently involved in their rituals, this means Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder is a part of daily life for over 1 million people every single day.

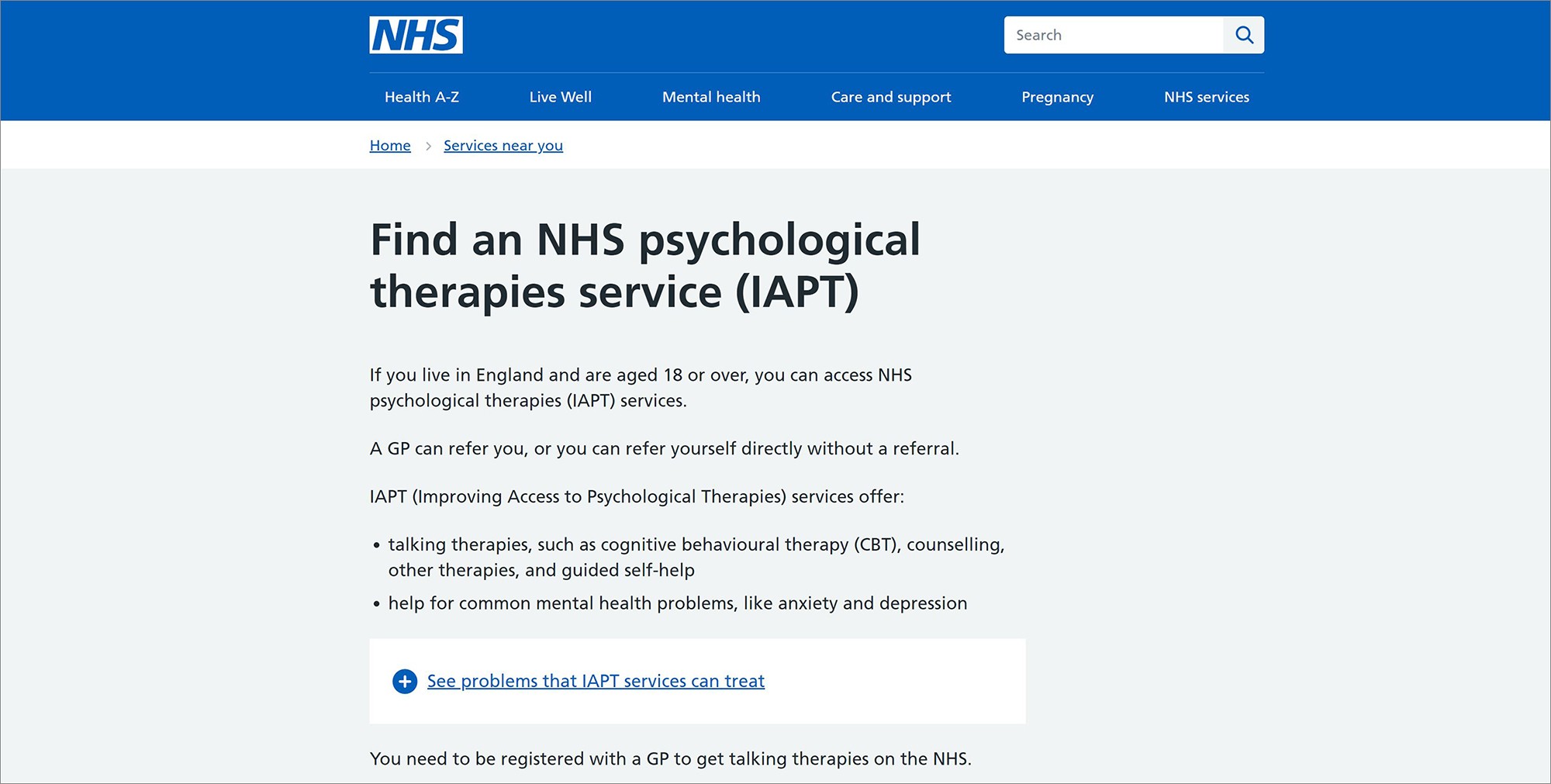

If you feel you might be affected by Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder you can find out about how OCD is diagnosed

elsewhere in this chapter. Below you can read more about the illness and aspects of living with OCD.

OCD – An Introduction

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (or more routinely referred to as OCD) is a serious anxiety-related condition where a person experiences frequent intrusive and unwelcome obsessional thoughts, commonly referred to as obsessions.

Obsessions are very distressing and result in a person carrying out repetitive behaviours or rituals in order to prevent a perceived harm and/or worry that preceding obsessions have focused their attention on. Such behaviours include avoidance of people, places or objects and constant reassurance seeking, sometimes the rituals will be internal mental counting, checking of body parts, or blinking, all of these are compulsions.

Compulsions do bring some relief to the distress caused by the obsessions, but that relief is temporary and reoccurs each time a person’s obsessive thought/fear is triggered. Sometimes over time the compulsions can become more of a habit where the original obsessive fear and worry has been forgotten, in this instance compulsions are often completed to enable the individual to feel ‘just right’, the key word being ‘feel’.

It’s worth pointing out that there is sometimes obvious correlation and logic between the obsession and compulsion, but other times there will be no logic at all between the two.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder presents itself in many guises, and certainly goes far beyond the common perception that OCD is merely a little hand washing, checking light switches or having spotless houses or a characteristic of someone who is a little fastidious. In fact, if a person is suffering with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder then it will be impacting on some or all aspects of their daily life, sometimes becoming severely distressing leading to some nature of impairment or even disablement for hours at a time, each and every day. It is for this reason and level of impact on a person that makes OCD a disorder.

The condition can be so disabling that back in 1990 the World Health Organisation ranked Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in the global top ten leading causes of disability in terms of loss of income and quality of life. In fact back then it went on to suggest that OCD was the fifth leading cause of burden for women in developed countries. More recently the World Health Organisation went on to state that anxiety disorders (including Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder) are the sixth largest cause of disability, and that more women than men are affected.

Despite the severity of OCD, popular culture frequently makes references to certain celebrities being ‘a little OCD’, such comments fail to take into account the fact that the ‘d’ in OCD means disorder. Such comments in popular culture do nothing to accurately raise awareness and are not only unhelpful but can be both damaging and stigmatic to those that suffer and add to the trivialisation of OCD.

A disorder is actually defined as An illness that disrupts normal physical or mental functions, and it is fair to say OCD does exactly that!

Disorder – An illness that disrupts normal physical or mental functions.Oxford English Dictionary

Based on current estimates for the UK population, there are potentially around three quarters of a million people living with OCD at any one time. But it is worth noting that a disproportionately high number of those, about 50% of all these cases, will fall into the severe category with less than a quarter being classed as mild cases.

OCD starts to become problematic and impacting on a person’s life on average during late adolescence for men and during their early twenties for women, although the age of onset covers a wide range of ages, with development of the disorder for some children as young as six. OCD will impact on individuals regardless of gender or social or cultural background and is now thought to affect slightly more females than males.

It used to be the case that sufferers would go undiagnosed for many years, partly because of a lack of understanding of the condition by both the individual themselves and amongst health professionals, but also partly because people went to great lengths to hide their symptoms. They would hide symptoms because of the intense feelings of embarrassment, guilt and sometimes even shame associated with what pre-internet times used to be called the ‘secret illness’.

This used to lead to delays in diagnosis of the illness and delays in treatment, with a person often waiting an average of 10–15 years between symptoms developing and seeking help.

Thankfully, partly through increased awareness from charities like OCD-UK and perhaps because information is now easier to access online, people are getting diagnosed much sooner, even if that is sometimes unofficially self-diagnosed.

To sufferers and non-sufferers alike, the thoughts and fears related to some aspects of OCD can often seem profoundly shocking, for example unwanted fears of hurting a loved one, or a child. It must be stressed, however, that they are just thoughts – not fantasies or impulses which will be acted upon, just unwanted intrusive thoughts which we talk about in the next page.

It is fair to say that to some degree OCD-type symptoms are probably experienced at one time or another by most people, especially in times of stress where they have succumbed to the seemingly nonsensical need to perform an odd and often unrelated behaviour pattern, which is why we often hear the really unhelpful phrase ‘everybody is a little bit OCD’. However, OCD itself can have a totally devastating impact on a person’s entire life, from education, work and career enhancement to social life and personal relationships, which is why such a phrase is spectacularly inaccurate!

The key difference that segregates little quirks, often referred to by people as being ‘a bit OCD’ from the actual disorder is when the distressing and unwanted experience of obsessions and compulsions impacts to a significant level upon a person’s everyday functioning causing great distress – this represents a principal component in the clinical diagnosis of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder.

What to read next: